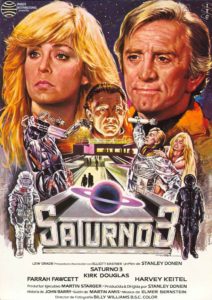

Today, I wanted to write a retrospective review and commentary about a much-maligned movie from 1980 – Saturn 3.

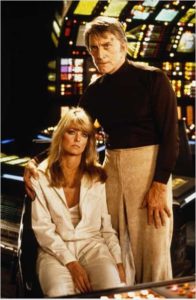

The film stars the stunning Farrah Fawcett (in the prime of her beauty), 64-year-old Kirk Douglas (whose acting skills are underutilized in this film), and a 40-ish Harvey Keitel (whose voice we never hear – more on that later).

First, the history. The film was based on a story by sci-fi film pioneer and Oscar-winning set designer, John Barry, who also started out as the film’s director. But early in production, Barry and Kirk Douglas had disagreements, and the studios pulled Barry and replaced him with Stanley Donen. Sadly, Barry went back to production on The Empire Strikes Back and fell ill on set, dying suddenly at the young age of 43.

The movie hit box offices in February 1980 in the US, and a few months later in the UK. The production of Saturn 3 was plagued with problems and bad timing. The studio began the project hoping to cash in on the sci-fi mania sweeping the globe. It was meant to piggy-back off of the success of Alien in the US. But another project the studio had in production went over budget, and Saturn 3 had to give up some of its own budget. The film was behind schedule constantly, as the robot required so much attention and was in so many scenes. There was reportedly much drama about nudity, with Douglas insisting on appearing half- or not clothed, and similarly demanding that Fawcett strip down (he allegedly said “What do you mean she won’t take her clothes off. She’s only a fucking TV actress. I’ll rip her clothes off!”)

And the problems didn’t end there. The studio didn’t like Keitel’s accent, and they asked him to do voice-over work in post-production. He refused, so they re-dubbed his entire presence in the film with British actor Roy Dotrice. Rumors swirled that Keitel and the studio executives were hostile to one another, leading to his refusal to cooperate.

There were many other production woes. The script was rewritten several times, with each one getting farther and farther from the original story. The phenomenal Elmer Bernstein (Oscar-winning composer and conductor) wrote a score and recorded the soundtrack, but the studio scrapped nearly all of it. Two long scenes were cut from the film prior to its release (some believe this was a fatal wound). And the special effects (which weren’t very special) wound up looking cheesy and cheap.

When the film hit theaters, it made a measly $9 million. Even by 1980 box office standards, it was a flop. Alien made $79 million in the US alone the year before. And critics hated Saturn 3, as well, meaning that the studio couldn’t even float the idea that it was a critical success despite its lackluster earnings.

But is that all there is to the story of Saturn 3? Is it worthless?

I don’t think so. I watched it again recently while researching something for my books. And I came away from it with a feeling I hadn’t felt in a long time. And when a movie can give you a feeling, it’s at least doing SOMETHING right.

In the 70s and 80s, sci-fi was trying to find its identity. The springboard of Star Trek and Star Wars caused the genesis of a new genre in film and television. And because the stories were still new to audiences, writers and producers experimented to try and find the right tropes. The action-packed Star Trek series became the awful, navel-gazing and dull Star Trek: The Motion Picture. But some of those experimental stories (speculative fiction) were quite effective in presenting unique questions for the audience.

What does it mean to be human?

Is the human existence limited to the meat-and-blood machine we inhabit?

What is humanity’s existence on earth in the future?

Is emotion purely human, or can machines feel them?

These kinds of questions are at the heart of many of the science fiction WRITING leading up to the film and television productions that have become so popular. Scenes that depict long periods of isolation don’t make great action sequences for popcorn. But that might very well be the future of humans in space. Dialog between characters that illustrate the philosophical questions facing humanity don’t pair well with Milk Duds and Goobers. But they cut to the core of the existential questions that fuel some of the best science fiction written in the last fifty years.

While watching Saturn 3, I felt the same thing I felt in the 1970s and 80s. A contradictory mix of despair and hope. Despair at the bleak and brutal future we may be destined for. But hopeful that technology and ingenuity might someday make interplanetary travel not just a reality, but commonplace.

That feeling still gets me going and inspires story ideas. It’s a heady mix of fear and excitement. It’s the chill I get in the pit of my stomach when I imagine myself isolated up there on that rock with Farrah (ok, the chill isn’t the only thing I feel when imagining myself alone on a space station with Farrah).

In the end, I think that Saturn 3 had real merit as a science fiction story. It makes me think. It challenges my ideas of humanity and our place in the universe. It forces me to question things I previously assumed and took for granted.

Isn’t that what science fiction is supposed to do? Isn’t “speculative fiction” all about making us ask questions? If so, then at least by that measure, Saturn 3 is a success. Maybe not an over-achiever. But a success.